The Celestial Globe

Inspired by the sphere of constellations held aloft by the second-century Roman sculpture known as the Farnese Atlas, the Celestial Globe spotlights the link between those ancient skies and modern astronomy.

The Cosmic Axis Takes Us for a Spin

The Earth rotates on an axis defined by its north and south poles, and this motion makes the stars seem to circle around a single, unmoving spot in the night sky. The celestial hub of this fundamental motion responsible for day and night was known to the ancients, who also used it to devise the cardinal directions.

Atlas, one of the Titans in ancient Greek myth, was said to hold up the heavens, which are portrayed as the celestial globe of the Farnese Atlas, a Roman sculpture from the second century A.D. in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, Italy. With the south pole of the sky supported on his back and the sky’s north pole at the top of globe, Atlas symbolizes the cosmic axis around which the sky seems to turn.

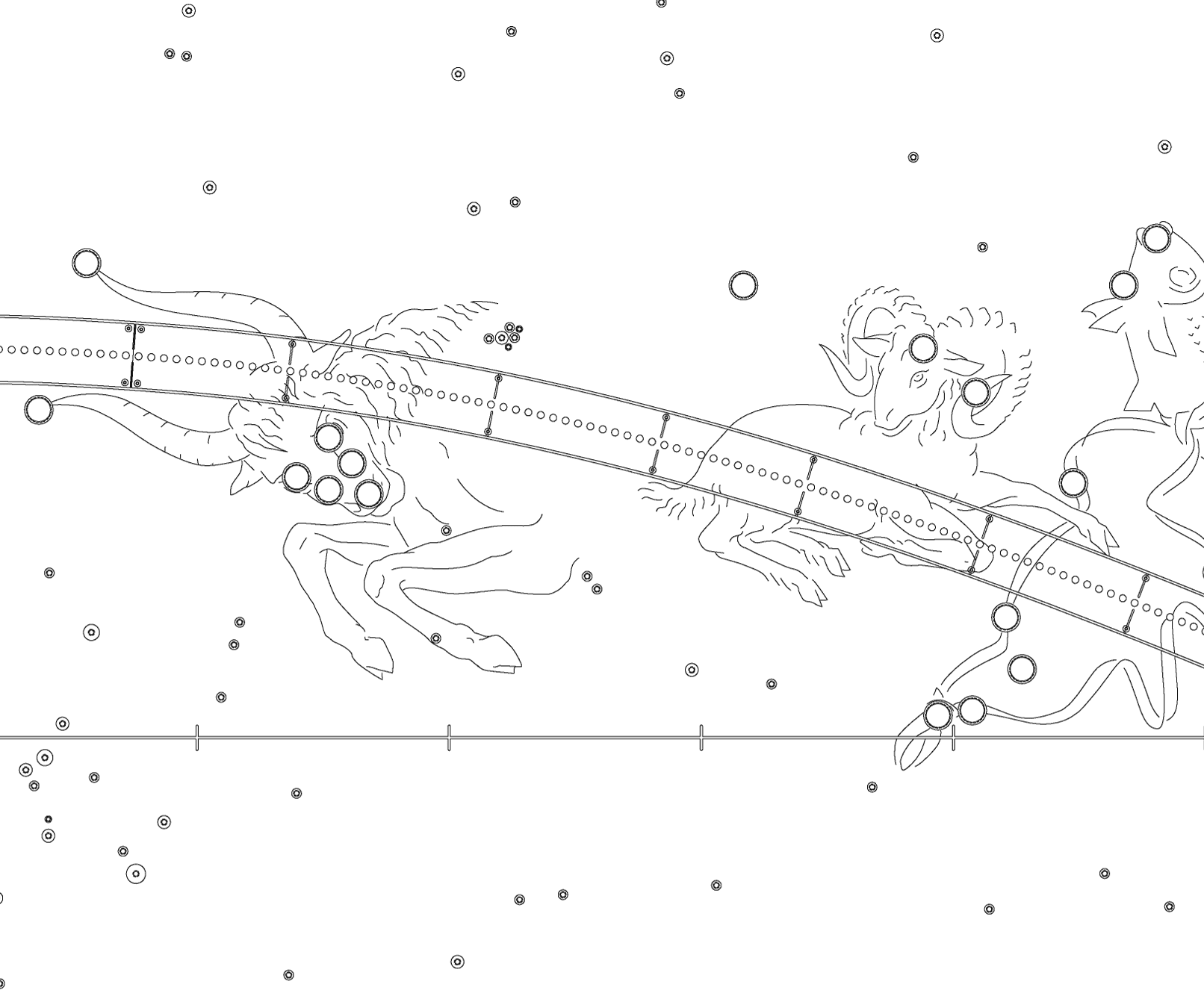

Constellations: Landmarks in the Sky

Constellations are configurations of stars that turn the wilderness of the night sky into recognizable patterns. These figures were used to find directions, follow the seasons, and track the motions of the Sun, Moon, and planets. Affiliated with myth, the constellations adopted by the ancient Greeks are still used to map the sky. Eighty-eight are now astronomically official. All of them make appearances in Griffith Observatory’s Samuel Oschin Planetarium.

The oldest known images of the ancient Greek constellations are accurately mapped on the celestial globe of the Farnese Atlas. Its 46 constellations appear on the Celestial Globe, Cindy Ingraham Keefer’s massive and monumental sculpture in Gravity’s Stairway at Griffith Observatory. Supported on a massive pole, it rotates as the ancient Greeks imagined the sky to turn in Atlas’s grip.