Teacher Resources

Whether or not your class is participating in one of our school programs, Griffith Observatory has resources and activities to make each student’s STEM learning richer and more inspiring.

Speaking Like an Astronomer

To think like an astronomer, your students need to know the language. It’s a good idea to have your students review the Glossary of Terms used in the school program before their visit. A fun activity is to assign one term per student or group of students. Have them create an illustration for the definition. Show the class the illustrations. Have them write down on a piece of paper the term that goes with each one. Make a class book out of the illustrations.

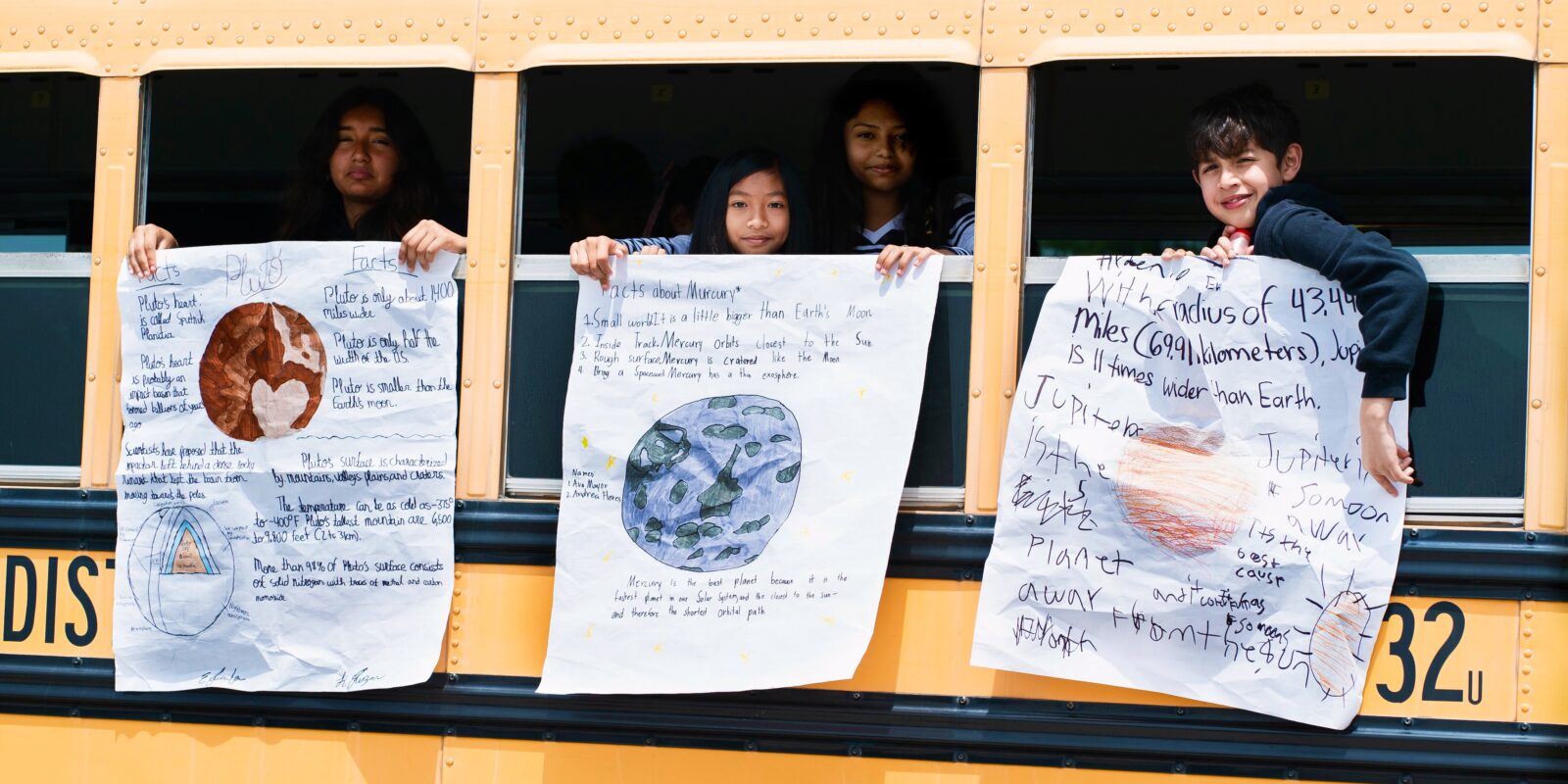

Be A Spacecraft (Part 1)

Have students look up the properties of each of the eight planets plus Pluto, including their size, distance from the Sun, and a few facts about them. Write down the information for each planet on index cards in preparation for your visit to Griffith Observatory. Identify space missions that have visited each planet. Did the spacecraft fly by, orbit, or land? When? What mission has gone the farthest? What was the first mission to land on another planet?

Where in the building: Gunther Depths of Space exhibits

When you visit Griffith Observatory, use these cards in Be a Spacecraft (Part 2) by re-enacting the historical sequence of solar system exploration.

Be A Spacecraft (Part 2)

The Solar System Lawn Model shows the relative size of the orbits of the planets (and Pluto) around the Sun. The center of the solar system is located in front of the Observatory’s North Doors. Students can compare the relative distances of the planets by standing on the inlaid bronze plaques and orbit lines. The Lawn Model is designed to complement the planet models scaled for size in the Gunther Depths of Space gallery. Ask the students why it is difficult to show the size of the planets and their orbits to scale in one exhibit.

(ANSWER: Any exhibit showing the planets’ size to scale would be much too large for the front lawn!)

Where in the building: Solar System Lawn Model (front lawn), Gunther Depths of Space exhibits

WANTED: Elements

After learning about the periodic table, each student chooses an element and creates a WANTED poster that describes the properties of that element but not the element’s name. Each student presents the poster to the class, and students try to identify elements from the information provided on the WANTED poster.

Where in the building: Ahmanson Hall of the Sky exhibits

Movement of the Sun

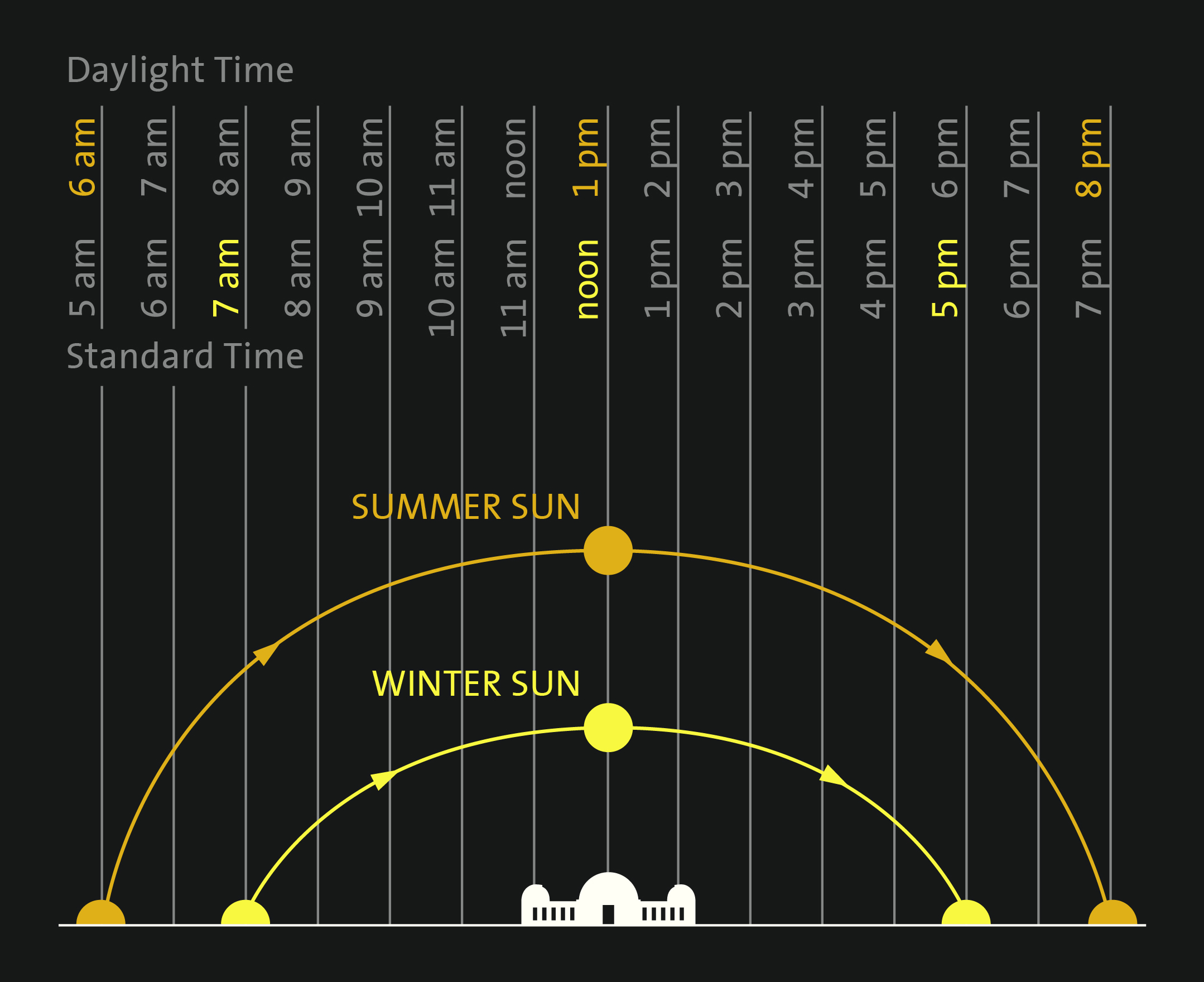

To show students that the position of the Sun changes from season to season, choose a classroom window or a place on the playground where students can observe and mark where the Sun is in the sky over the course of one day. Then, do the same thing at the same time each day throughout the year. Mark the place every two weeks for several months or the whole school year.

Where in the building: Gottlieb Transit Corridor and Observatory sundial (lawn); Sun and Stars Paths exhibit (Ahmanson Hall of the Sky)

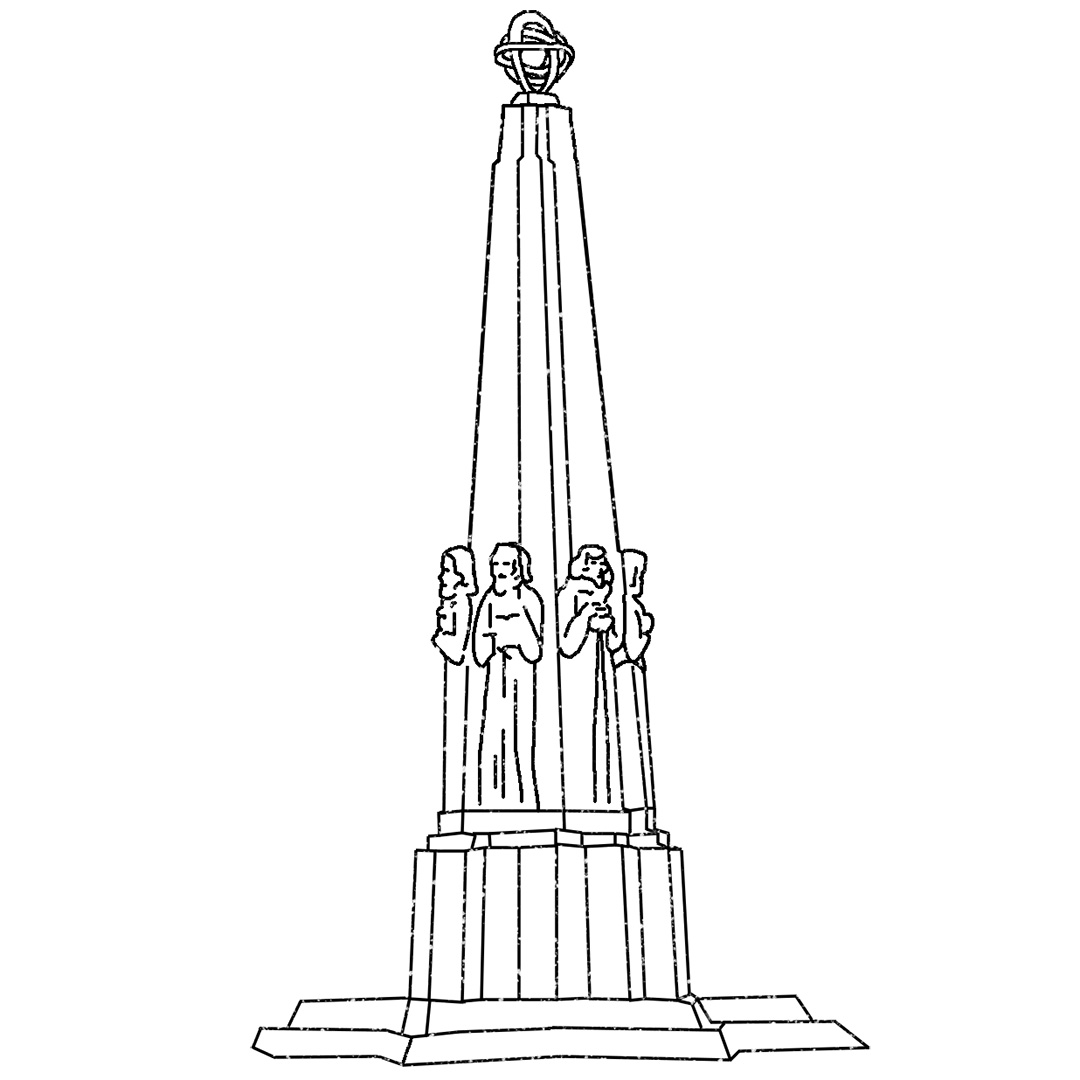

Monumental Astronomers

Upon arrival at Griffith Observatory students see first the Astronomers Monument: A large concrete sculpture on the front lawn that spotlights six prominent astronomers from history. Here is some information about these astronomers and other key players essential to their success.

- Hipparchus (c. 150 B.C.E.), a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician, used mathematics to discover a slow wobble of the Earth’s axis that causes star positions to appear to shift over time. He used Babylonian astronomical knowledge and observing techniques.

- Nicholas Copernicus (1473-1543) was a Polish astronomer who reorganized the solar system and put the Sun at its center. His work was based on his and others’ observations of the motions of the planets and previous theories from Islamic and Greek astronomers.

- Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), an Italian astronomer, mathematician, and philosopher, was the first to observe the sky methodically with a telescope and analyze, combine, and publish these observations.

- Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), a German astronomer and mathematician, discovered the fundamental laws of planetary motion, which describe how the planets move around the Sun. Kepler’s (and Galileo’s) work confirmed Copernicus’s theories and led Isaac Newton to his discoveries.

- Isaac Newton (1642-1727), an English astronomer, philosopher, and mathematician, discovered the laws of gravitation and motion which apply to all objects across the universe.

- William Herschel (1738-1822), a German-British astronomer, discovered the planet Uranus, infrared radiation, and the shape of the Milky Way Galaxy based on observations and measurements. His sister, Caroline Herschel, provided valuable assistance and also became the world’s first professional female astronomer in her own right. She was the first woman to discover a comet, a feat she accomplished eight times, and catalogued many celestial objects.

While circling the monument, discuss these major scientific accomplishments. Ask your students: If you were a scientist, what would you focus your research on?

Where in the building: Astronomers Monument & Sundial (lawn)

Using the Sun to Tell Time

Using the Sundial, students may estimate the current time without looking at a watch. Teacher: Check a watch to compare accuracy of the Sundial. Ask the students how close the times are and why they are different?

Using the Sundial, students may estimate the current time without looking at a watch. Teacher: Check a watch to compare accuracy of the Sundial. Ask the students how close the times are and why they are different?

(ANSWER: We use different “time zones” to approximate the local time, but the actual time can vary depending on where you are located in your time zone. In addition, at different times of the year the Sun can be slightly ahead or behind the time determined from the local meridian, an imaginary north-south line.)

Where in the building: Astronomers Monument & Sundial (lawn)

Through a Telescope

Come back to the Griffith Observatory at night and bring family and friends! The Zeiss telescope and portable telescopes at Griffith Observatory are free and open to the public every clear night the Observatory is open until 9:45 p.m., though it is advisable to arrive before 9:00 p.m. to ensure a look through a telescope. You could also come for one of our monthly public star parties.

Come back to the Griffith Observatory at night and bring family and friends! The Zeiss telescope and portable telescopes at Griffith Observatory are free and open to the public every clear night the Observatory is open until 9:45 p.m., though it is advisable to arrive before 9:00 p.m. to ensure a look through a telescope. You could also come for one of our monthly public star parties.

Use our list of local astronomy clubs to find one near you that sponsors star parties and let your students and their families know.

Marking the Motion of the Sky

Each day, when the Sun reaches its highest point in the sky, Griffith Observatory’s instruments in the Gottlieb Transit Corridor come to life. Ask a Museum Guide when the Local Noon demonstration will occur on the day of your visit. The corridor is to the west of the building just outside of the café and gift shop.

Each day, when the Sun reaches its highest point in the sky, Griffith Observatory’s instruments in the Gottlieb Transit Corridor come to life. Ask a Museum Guide when the Local Noon demonstration will occur on the day of your visit. The corridor is to the west of the building just outside of the café and gift shop.

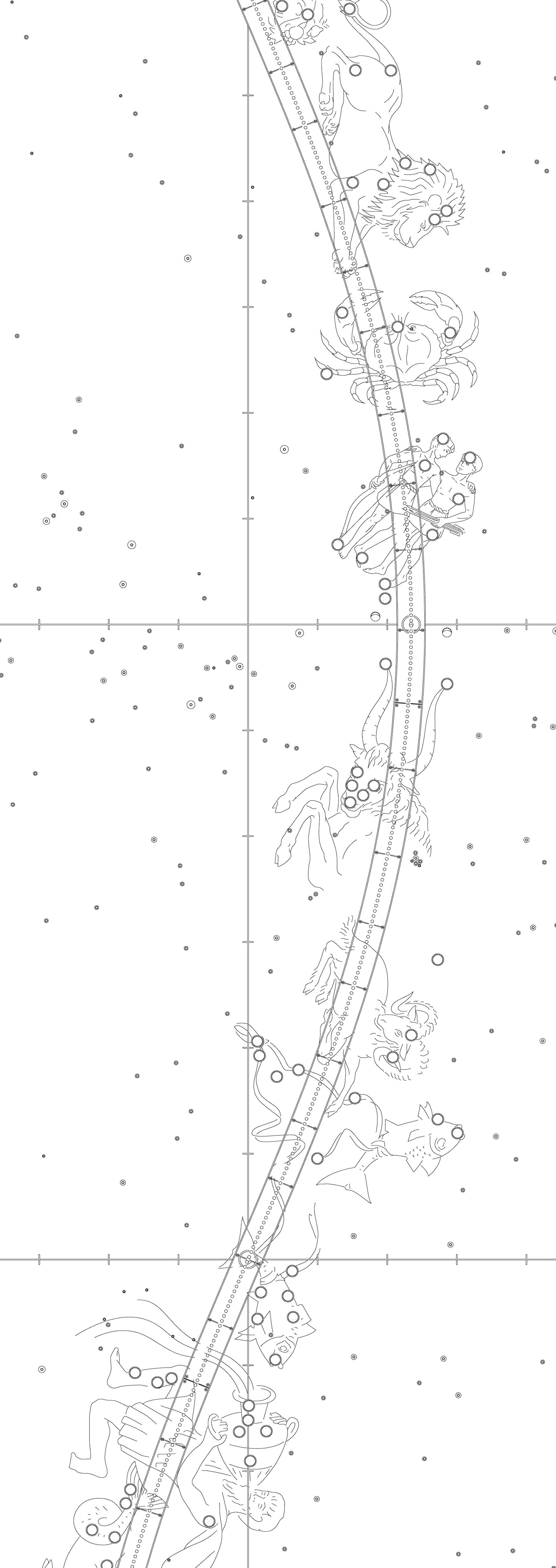

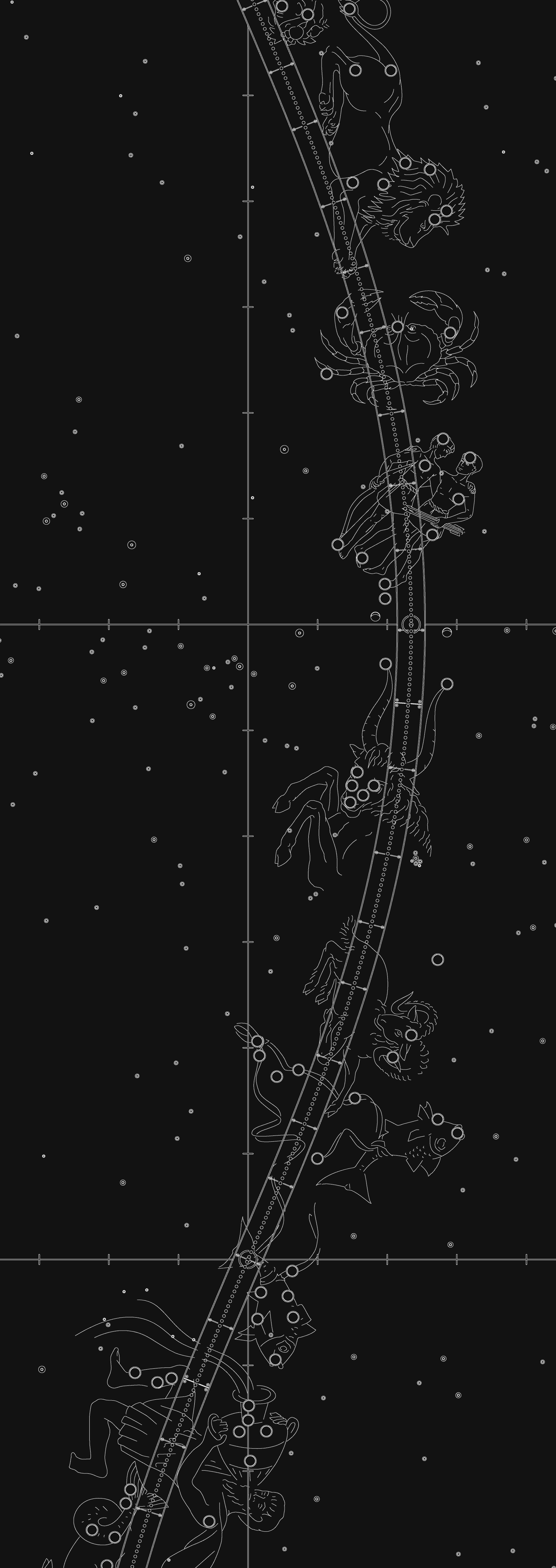

The Gottlieb Transit Corridor immerses students in the motions of the Sun, Moon, and stars across the sky and demonstrates how these motions are linked with time and the calendar. Using the Meridian Arc, students will observe the Sun’s daily passage (transit) across the north-south line (meridian) at local solar noon and will see on the Ecliptic Chart which constellation the Sun currently resides in. The Meridian Arc also demonstrates how the Sun changes its elevation seasonally along the north-south arc that bridges the sky (celestial meridian). Similar observations have been made by people all over the Earth since antiquity.

For an extension activity, see our Zodiac Constellation Activity Chart, a crafty observing tool that helps students understand the unseen sky.

Where in the building: Gottlieb Transit Corridor

Inventing Life Forms

Students imagine how life might have evolved on planets with different conditions from those on Earth. Begin by providing an overview of the different kinds of planets in our solar system and in other solar systems.

Then, working in groups, students invent a life form that would adapt to the conditions on an alien world. Students draw, describe, write a story about, and/or role play as the creature they have invented and then describe why it would survive. For a quieter, individual-work approach, see Make Your Own Exoplanet & Extraterrestrial Life.

Where in the building: Gunther Depths of Space

Water Cycle Game

The complexity of Earth’s water cycle becomes clear as students discover the fate of the Earth’s water in an interactive, role-playing game. Students “become” water as it moves through the cycle: Ice trapped in a glacier for millennia, liquid water drawn up tree roots and, through photosynthesis, turned into food, or water flushed down the toilet and into the sewer!

The complexity of Earth’s water cycle becomes clear as students discover the fate of the Earth’s water in an interactive, role-playing game. Students “become” water as it moves through the cycle: Ice trapped in a glacier for millennia, liquid water drawn up tree roots and, through photosynthesis, turned into food, or water flushed down the toilet and into the sewer!

To review the water cycle, see this Water Cycle coloring page.

Space Charades

In this activity, students are astronauts completing tasks inside and outside a space shuttle. But oh no—your radios are malfunctioning and astronauts outside the shuttle can’t communicate verbally with the interior crew! Designate a student or students as astronaut(s) outside the shuttle. Have them think of a short story and then act out their “critical mission updates” to the interior crew with gestures only. Can the interior crew determine what the astronaut(s) outside the shuttle are trying to say and give them the help they need in time?

Secret prompts may be helpful: Asteroids approaching! Sample acquired! Aliens encountered!

Make Your Own Comet

Here’s the “recipe” from the Clues from Comets demonstration that you can do in the classroom.

Astronomy Resources on the Web

Check out these online astronomy educational resources from NASA, the Planetary Society, and other institutions.

Review Third-grade Standards

The Griffith Observatory field trip program assumes students are already familiar with concepts described in the third-grade standards.